This is what happens at Bolivian parties.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

A Little Subtraction, Part 1: Robbery

I was robbed last Tuesday night and lost my camera and Bolivian cell phone. If I had been the victim of normal pickpocketing, I don’t think I would have felt quite so shaken, but the robber was pretty aggressive. Willa (one of my housemates) and I took a bus and planned to do a transfer on the edge of the market area (which is known for robberies). We've done this a lot and never have to wait for the next bus. Last Tuesday, however, was the Aymara New Year (aka the Winter Solstice or, in the States, the Summer Solstice), which President Evo Morales declared a public holiday sometime in the last few years. Therefore, public transportation wasn’t running normally and Willa and I ended up stranded where we had intended to transfer. A simple solution would have been to take a taxi, but there were no safe taxis around. (A “safe taxi” is a marked one, indicating that it is dispatched by a company. An “unsafe” taxi, at least at night, is one with a generic sticker that says “taxi” which people slap on their cars when they want to make money transporting people.)

While waiting for a safe taxi, a man ran up and starting yanking at the camera bag I had around my neck. I thought it was inconspicuous/unattractive enough seeing as how it was small and I was holding it close to my body, but this man was not deterred. I tugged back and ended up on the ground, and then the guy ran away. Willa and I then looked more desperately for a marked taxi and, within a few minutes, the man reappeared and again pulled at my bag.

At that point I told Willa we just needed to leave, even if we had to do so on foot, and we began to walk in the direction of our home (which was a few miles away at that point). One of the men we passed exhorted us to escape because the thief was following. While I was grateful for the warning, that moment might actually have been the scariest part of the experience because I looked around and had no idea who was following us, where he might come, and when he might attack. There wasn’t much we could do, though, except continue walking.

Less than a block away, I asked Willa to lend me the sweater she had bought at the market earlier so that I might put it on and cover the camera bag but the thief appeared again, started yanking at my bag again, and would not let go. I ended up on the ground again (cussing a lot, I have to admit), and pulled back, in part to save my camera and in part to save my neck. The strap on my camera bag was thick, after all, and I did not relish the idea of being dragged, strangled, or cut.

On a certain level, I’m glad the plastic clasps on the bag broke and the thief got away. Ideally, the thief would have run away and not come back after the first robbery attempt but that didn’t happen. The man was aggressive, and he certainly didn’t care what happened to me.

In the end, Willa found us a safe taxi and we got back to our house. (I was so upset that I had stopped looking and was ready to walk all the way home.) I cried for a little while, called my travel insurance company to ask about making a claim, and then Willa and I went to visit the sisters next door for tea and, for lack of a better word, debriefing. The sisters told us stories about robberies/robbery attempts that they and their friends had experienced. These stories were strangely comforting, perhaps because they made me feel less stupid for having worn my camera bag on the outside of my clothes and more like I had joined the ranks of everybody else who lives in Cochabamba.

The rest of Tuesday night was pretty horrible in terms of sleep, but I’m better now. Still nervous at times, still a little spooked by quick movements in my direction, but better. I’ve lost a camera and a cell phone but I’m safe and--trying to look even more on the bright side—now that I’ve subtracted a camera from my possession, I can subtract a little weight from my bag in the face of increasingly strict weight restrictions on airlines. Yay. Just what I was looking for when Willa and I headed to the market Tuesday night.

While waiting for a safe taxi, a man ran up and starting yanking at the camera bag I had around my neck. I thought it was inconspicuous/unattractive enough seeing as how it was small and I was holding it close to my body, but this man was not deterred. I tugged back and ended up on the ground, and then the guy ran away. Willa and I then looked more desperately for a marked taxi and, within a few minutes, the man reappeared and again pulled at my bag.

At that point I told Willa we just needed to leave, even if we had to do so on foot, and we began to walk in the direction of our home (which was a few miles away at that point). One of the men we passed exhorted us to escape because the thief was following. While I was grateful for the warning, that moment might actually have been the scariest part of the experience because I looked around and had no idea who was following us, where he might come, and when he might attack. There wasn’t much we could do, though, except continue walking.

Less than a block away, I asked Willa to lend me the sweater she had bought at the market earlier so that I might put it on and cover the camera bag but the thief appeared again, started yanking at my bag again, and would not let go. I ended up on the ground again (cussing a lot, I have to admit), and pulled back, in part to save my camera and in part to save my neck. The strap on my camera bag was thick, after all, and I did not relish the idea of being dragged, strangled, or cut.

On a certain level, I’m glad the plastic clasps on the bag broke and the thief got away. Ideally, the thief would have run away and not come back after the first robbery attempt but that didn’t happen. The man was aggressive, and he certainly didn’t care what happened to me.

In the end, Willa found us a safe taxi and we got back to our house. (I was so upset that I had stopped looking and was ready to walk all the way home.) I cried for a little while, called my travel insurance company to ask about making a claim, and then Willa and I went to visit the sisters next door for tea and, for lack of a better word, debriefing. The sisters told us stories about robberies/robbery attempts that they and their friends had experienced. These stories were strangely comforting, perhaps because they made me feel less stupid for having worn my camera bag on the outside of my clothes and more like I had joined the ranks of everybody else who lives in Cochabamba.

The rest of Tuesday night was pretty horrible in terms of sleep, but I’m better now. Still nervous at times, still a little spooked by quick movements in my direction, but better. I’ve lost a camera and a cell phone but I’m safe and--trying to look even more on the bright side—now that I’ve subtracted a camera from my possession, I can subtract a little weight from my bag in the face of increasingly strict weight restrictions on airlines. Yay. Just what I was looking for when Willa and I headed to the market Tuesday night.

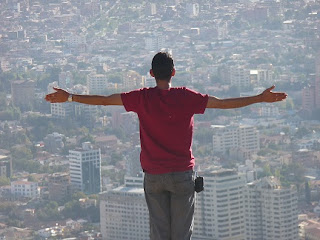

| We went up the mountain in the national park (the most uninviting, unmarked national park I've ever seen) and what do you think we saw? A giant slide! A happy picture for a not so happy blog entry |

Sunday, June 19, 2011

A Tale of a Cake and My Face

Once upon a recent time, a woman named Meghan went to Bolivia. She hoped the people there would be nice and, indeed, they did seem very nice! Some of her new friends even took her out for lunch and dessert on June 15th, her 25th birthday, but the celebration did not end there for the following Sunday, one of Meghan's housemates made a journey to "Dumbo," the restaurant/bakery/ice cream parlor in downtown Cochabamba named after the same loveable elephant who once appeared in Disney movie, to purchase a birthday cake. Later that evening, Meghan, her housemates, two Maryknoll sisters and a Maryknoll lay missionary sat down to enjoy their dessert, but the Maryknollers, so influenced by Bolivian culture which dictates pushing a person's face into their birthday cake, hatched an evil plan (*see disclaimer below) to push Meghan's face into her own cake! And so it came to pass. You can see the pictures below. The end.

*Disclaimer: For the purpose of telling a good story, Meghan likes to blame the cake and face incident on the Maryknollers, but Meghan actually thought sticking her face into a cake sounded like fun.

*Disclaimer: For the purpose of telling a good story, Meghan likes to blame the cake and face incident on the Maryknollers, but Meghan actually thought sticking her face into a cake sounded like fun.

Saturday, June 18, 2011

Going to Prison

Was it the coca tea I frequently drink? Was it the bootleg copies of The King's Speech and Julie and Julia that Willa and I bought around town? Was it the fact I walked through the street spitting mandarin orange seeds onto the ground and, just yesterday, snuck in a few shots from the roof of the Santa Teresa convent (even though I was supposed to pay to take pictures on our tour)? Nope. None of the above got me to prison. (FYI: coca tea and coca products that are not drugs are legal, Bolivian copyright laws only protect Bolivian work, seeds are just about the most innocuous thing you'll see on the ground here, and, as far the the convent picture-taking episode goes, well....I figure the nuns don't own the skyline)

My two trips to prison this week were actually voluntary, part of the new work I'm trying out since I stopped working with the little kids. So far, I like being at the prison more the than I liked being at Pedacito, despite the fact that there's not much to like about the prisons themselves.

When you go to prison (involuntarily) in Bolivia, of some things you get far less than in the States, and of some things you get far more. Let's start with the semi-positive: while in prison you get more time with your family and, in some senses, more freedom within the prison walls. More time with your family, though, doesn't necessarily mean more visiting hours...it can mean that your children live with you because there is no real foster care system in Bolivia and you lack family that take on the role of caregiver. Your children go to school during the day, and come back to the prison in the afternoon. You all live together in a cell. As far as more freedom is concerned, I suppose I can't make detailed comparisons since I've never visited a U.S. prison, but I'm pretty sure it doesn't looke like a market inside and that, essentially, is what the patio of the women's prison looked like. People congregated around plastic tables and chairs, children wandered around, and women sold things from alcoves and stands around the patio. Someone was even walking around with a pan of bread...I could have bought myself a snack! No one, from what I could see, was "behind bars"--that concept didn't even seem to exist.

Far less positive is the overcrowding, the long waits (usually two years) for trials, the sentences that don't fit the crimes, and the fact that prisoners are entitled to nothing, not even a bed or a cell. That's right. If you don't want to sleep on a mattress in the central patio, you have to pay. You have to pay for everything, in fact, including food, medicine, and other basics like toilet paper. You are given a stipend of about 6 Bolivianos/day, but 6 Bolivianos is less than a dollar. So how to do you make money? Well...if you're a woman, you can do laundry (people actually drop their laundry off at the prison), knit things, make crafts. If you're a man you can do craft things too, but you can also make furniture (which someone will haul out to the plaza in front of the prison so that people can browse and buy) or grills.

It's a different system, to say the least. My role in it on Tuesday was as part of a group that went to one of the men's prisons to weigh/measure young children and give out milk and vitamins. In the end, Hermana Maria Angeles, the nun in charge of prison ministry for the archdiocese, put me to work handing out used, donated shoes. I was under strict orders, though, to not give out shoes unless a child had tried them on and unless they fit. This proved harder than I thought it would be because fathers and children alike wanted whatever shoes they could get, even if a kid's toe was at the end of the shoe. It was difficult to say "no" a lot but, since every child I met had some kind of shoes on their feet already, I do think it was better to give the shoes to kids who would find them comfortable, at least for a little while.

Today, I didn't do much at the prison. I just went for mass and met some of the women. Mass was in the patio and it was nearly impossible to hear because the priest had no microphone, but a number of women showed up and took at seat on the plastic chairs (advertising Coca Cola) while several more looked on from the side. As we sat there, my mind wandered...I wanted to know what the women thought of the mass, what they thought of life in prison, what they thought of life in general. I'll let you know if I ever find out.

| An "illegal" picture |

When you go to prison (involuntarily) in Bolivia, of some things you get far less than in the States, and of some things you get far more. Let's start with the semi-positive: while in prison you get more time with your family and, in some senses, more freedom within the prison walls. More time with your family, though, doesn't necessarily mean more visiting hours...it can mean that your children live with you because there is no real foster care system in Bolivia and you lack family that take on the role of caregiver. Your children go to school during the day, and come back to the prison in the afternoon. You all live together in a cell. As far as more freedom is concerned, I suppose I can't make detailed comparisons since I've never visited a U.S. prison, but I'm pretty sure it doesn't looke like a market inside and that, essentially, is what the patio of the women's prison looked like. People congregated around plastic tables and chairs, children wandered around, and women sold things from alcoves and stands around the patio. Someone was even walking around with a pan of bread...I could have bought myself a snack! No one, from what I could see, was "behind bars"--that concept didn't even seem to exist.

Far less positive is the overcrowding, the long waits (usually two years) for trials, the sentences that don't fit the crimes, and the fact that prisoners are entitled to nothing, not even a bed or a cell. That's right. If you don't want to sleep on a mattress in the central patio, you have to pay. You have to pay for everything, in fact, including food, medicine, and other basics like toilet paper. You are given a stipend of about 6 Bolivianos/day, but 6 Bolivianos is less than a dollar. So how to do you make money? Well...if you're a woman, you can do laundry (people actually drop their laundry off at the prison), knit things, make crafts. If you're a man you can do craft things too, but you can also make furniture (which someone will haul out to the plaza in front of the prison so that people can browse and buy) or grills.

It's a different system, to say the least. My role in it on Tuesday was as part of a group that went to one of the men's prisons to weigh/measure young children and give out milk and vitamins. In the end, Hermana Maria Angeles, the nun in charge of prison ministry for the archdiocese, put me to work handing out used, donated shoes. I was under strict orders, though, to not give out shoes unless a child had tried them on and unless they fit. This proved harder than I thought it would be because fathers and children alike wanted whatever shoes they could get, even if a kid's toe was at the end of the shoe. It was difficult to say "no" a lot but, since every child I met had some kind of shoes on their feet already, I do think it was better to give the shoes to kids who would find them comfortable, at least for a little while.

Today, I didn't do much at the prison. I just went for mass and met some of the women. Mass was in the patio and it was nearly impossible to hear because the priest had no microphone, but a number of women showed up and took at seat on the plastic chairs (advertising Coca Cola) while several more looked on from the side. As we sat there, my mind wandered...I wanted to know what the women thought of the mass, what they thought of life in prison, what they thought of life in general. I'll let you know if I ever find out.

Sunday, June 12, 2011

"Vaca," No "Caca" (No More)

|

| On the bus--I'm not too hard to find. |

Now, I don't want to give a false impression of the state of the home. Considering the resources available, I think the women who work at Pedacito full-time do a good job (and a better job than I could probably do if Pedacito became my career). Some moments of chaos were inevitable. Nonetheless, some chaos probably could have been prevented--like the hour of chaose before bedtime in which the kids were running around like crazy, sticking their fingers into each other's butt cracks, and coming very close to stepping on the baby who was laying on the floor (and whom I was told not to touch so that he wouldn't become too attached to anyone before he went to bed). An alternative? Read. At least two children were interested in the story I started and if each adult had sat down with a book, I think whole house would have been calmer. Still, I can't know for certain, and I can't throw stones. I just know that I would have dreaded my remaining five weeks here if I had remained at Pedacito.

Thankfully, the director of the Maryknoll short term mission volunteer program was very understanding of my desire to leave and said that there are a lot of other things to get involved in here. This coming week, then, I'll be trying out some other kinds of work and piecing together a more part-time schedule. Adjusting to life here takes a lot of energy and can be draining, so even if I really wanted to work with little kids, I probably couldn't do it for a full forty hours per week, at least not so soon after my arrival.

Despite the fact that I will no longer be returning to Pedacito, I'm glad I gave it a try. There were plenty of memorable moments--some good, some bad--and I've acquired some stories I'll probably be telling for a while. (I also acquired some good self-knowledge that will be most helpful the next time I have the opportunity to work with kids.)

A couple funny stories can be lumped together by one theme: poop. Potty humor, for the most part, is not my thing. When you work with little kids, however, poop--or the possiblity of poop--is always with you, and so I turn once again to the title of my blog entry: "Vaca, no caca" was actually what a "tia" ("aunt" in Spanish and what the children call the adults who work at the home) said to one of the kids when they were learning the names of different animals. The tia would point to a picture of an animal and the children would repeat. We learned about "patos" (ducks), "gatos" (cats), "ovejas" (sheep), and several other animals, including "vacas" (cows). Someone, though, repeated "caca" instead of "vaca," which prompted the tia to say, in a somewhat reproachful tone: "Vaca, no caca." It was the funniest part of the day!

On Saturday, poop was an especially prominent theme. After lunch, Willa (one of my housemates) and I were told to take the youngest three children to the bathroom, sit them on their little baby potties, and not let them get up until they had pooped. (This, apparently, was to ensure that they wouldn't poop in their diapers.) I honestly don't know how long we stood there or how many times I said (following the lead of the tias) "Haz caca" (Poop.), "No puedes levantarte hasta que hagas caca" (You can't get up until you poop.), or "Has hecho caca?" (Have you pooped?), but the whole event culminated in only one of three children doing their "duty." Santiago, one of the other kids, just crossed his legs like his potty was a La-Z-Boy and José

(the youngest) ended up sticking his hands in what Matias had left in his potty.

|

| These are the three who had a duty to do. |

A couple hours later, Willa and I left. Our parting shot of the kids? Try hard to picture this: all 12 children and 5 adults piled into 1 minivan with 1 taxi driver on their way to an event at which some of the children were going to perform a dance. I waved goodbye enthusiastically.

|

| Matias and I got along very well (and not only when he was sleeping!) |

Tuesday, June 7, 2011

The light before the...?

For all my light-hearted blog entries about “no urinating” signs and landing on water, there’s some serious stuff going on here: a strike at the university, a hunger strike at the bank, women begging on the streets, children living with abuse. Though I’m not sure I’ll ever get to know the strikers or the women, or the myriad other groups longing and working for change, I will get to know the children, at least some of them.

Tomorrow, I start work at two children’s homes: Pedacito del Cielo (a home for children up to age five) and Corazón del Pastor (a home for girls ages 5-18). Both homes take in abused, abandoned, and orphaned children (as well as children whose parents, for one reason or another, can’t support them for a time) and have a special interest in helping children with HIV/AIDS. For now, most of my time will be spent at Pedacito del Cielo (PDC). When the girls go on winter break in a few weeks, though, I’ll be teaching them dance!

This is what I’m most looking forward to. Cochabamba is new to me. Bolivian culture is new to me. These children will be new to me, but dance will not be. It’s my portable comfort zone. More importantly, I think dance is something the girls and will be able to share. Sure, I’ll be stepping into a teacher role and facilitating “class” (whatever that my look like), but I have no doubt that I’ll walk away from the experience having learned a thing or two from the girls. Each individual, after all, moves in their own way, and so does every culture. Dance, like language, is a form of communication.

Tomorrow, then, marks the end of my “insulated” time in Bolivia, the end of living like a tourist, disengaged from the community that surrounds me. This time hasn’t been bad; at moments, I’ve even seen it as the light before the dark, a preservation of my comfortable way of life before opening myself up to the lives of children who face darker challenges then the ones I faced as a child. I’ve begun to wonder, though, what this does to me…that is, how considering something potentially dark and depressing affects my ability to be open what is good and joyful. So…I’m changing my way of thinking. This is not the light before the dark, but rather the light before the question mark or, as the title of this blog entry states, “The light before the…?”

Tomorrow, I start work at two children’s homes: Pedacito del Cielo (a home for children up to age five) and Corazón del Pastor (a home for girls ages 5-18). Both homes take in abused, abandoned, and orphaned children (as well as children whose parents, for one reason or another, can’t support them for a time) and have a special interest in helping children with HIV/AIDS. For now, most of my time will be spent at Pedacito del Cielo (PDC). When the girls go on winter break in a few weeks, though, I’ll be teaching them dance!

This is what I’m most looking forward to. Cochabamba is new to me. Bolivian culture is new to me. These children will be new to me, but dance will not be. It’s my portable comfort zone. More importantly, I think dance is something the girls and will be able to share. Sure, I’ll be stepping into a teacher role and facilitating “class” (whatever that my look like), but I have no doubt that I’ll walk away from the experience having learned a thing or two from the girls. Each individual, after all, moves in their own way, and so does every culture. Dance, like language, is a form of communication.

Tomorrow, then, marks the end of my “insulated” time in Bolivia, the end of living like a tourist, disengaged from the community that surrounds me. This time hasn’t been bad; at moments, I’ve even seen it as the light before the dark, a preservation of my comfortable way of life before opening myself up to the lives of children who face darker challenges then the ones I faced as a child. I’ve begun to wonder, though, what this does to me…that is, how considering something potentially dark and depressing affects my ability to be open what is good and joyful. So…I’m changing my way of thinking. This is not the light before the dark, but rather the light before the question mark or, as the title of this blog entry states, “The light before the…?”

|

Monday, June 6, 2011

I've Seen Jesus!

That's right. I've seen him. He's tall, very pale, and rather stiff, if you ask me. See for yourself in the picture below:

Okay, okay--this isn't really Jesus, just the Cristo de la Concordia statue modeled after the one in Rio. You may think the statue is Rio is more impressive, seeing as how it looms over the ocean and all, but remember: the Cristo in Cochabamba is taller! It's the tallest Cristo in the world! Take that, Brazil.

The brave and strong can hike up the 1200+ stairs to the Cristo. Some Maryknoll langugage institute students in my group did it, but, because of some bug that's attacked my GI system over the last 24 hours, I'm not feeling so strong right now and I took the teleferico instead of the stairs.

Once you get to the base of the Cristo, you can pay 1.5 Bolivianos (7 Bolivianos=$1) and climb more stairs inside the statue. Now, if you think the inside of the Cristo sounds like a great place to go to the bathroom, you're not alone. Apparently, peeing inside the statue has been a problem, and a sign warns you of a 50 Boliviano fine for relieving yourself on the way up the stairs. So don't do it! It's not worth it! You can buy yourself a nice dinner for 50 Bolivianos (and you'll find yourself a nice bathroom at the restaurant).

Okay, okay--this isn't really Jesus, just the Cristo de la Concordia statue modeled after the one in Rio. You may think the statue is Rio is more impressive, seeing as how it looms over the ocean and all, but remember: the Cristo in Cochabamba is taller! It's the tallest Cristo in the world! Take that, Brazil.

The brave and strong can hike up the 1200+ stairs to the Cristo. Some Maryknoll langugage institute students in my group did it, but, because of some bug that's attacked my GI system over the last 24 hours, I'm not feeling so strong right now and I took the teleferico instead of the stairs.

Once you get to the base of the Cristo, you can pay 1.5 Bolivianos (7 Bolivianos=$1) and climb more stairs inside the statue. Now, if you think the inside of the Cristo sounds like a great place to go to the bathroom, you're not alone. Apparently, peeing inside the statue has been a problem, and a sign warns you of a 50 Boliviano fine for relieving yourself on the way up the stairs. So don't do it! It's not worth it! You can buy yourself a nice dinner for 50 Bolivianos (and you'll find yourself a nice bathroom at the restaurant).

|

| Stairs inside the statue (with "no urinating" sign on right) |

|

| View of Cochabamba from the Cristo |

Saturday, June 4, 2011

Friday, June 3, 2011

If You See An Ocean, You're Not in Bolivia

Of course I know Bolivia is a landlocked country. That didn’t matter, however, when I fell asleep on my overnight flight from Miami to La Paz. In my dreams, we approached La Paz flying over the ocean. It was beautiful, actually: bright, sunny, sparkling waves, impressive skyline. We flew rather close to the water, but this didn't concern me because, in my dream, flying low was simply part and parcel of arriving in La Paz. The pilot, however, brought the plane a little too low and a large wave came up to meet us, lifting the plane as if it was a surfboard.

Though water began to fill the plane, no one, including myself, was afraid, only slightly annoyed at what we had to do: gather our belongings, put on lifejackets, and evacuate. I considered leaving some things behind to evacuate quicker, but I hated the thought of my laptop getting destroyed and hastily gathered my things before heading to the airplane door and exiting via yellow emergency escape slide.

Once outside the plane, we walked the rest of the way to the airport, trudging through the surf. Laptop in hand I explained to some guy walking beside me that I thought something like this would happen and that I regretted not putting my laptop in a plastic bag to safeguard it from the water.

At that point, I woke up and found that, despite the plane still being up in the air and my laptop resting safe in my bag, my surroundings were not nearly as nice as in my dream. Outside, it was dark and, inside the plane, I was sandwiched between the window and a stocky man whose left elbow had been encroaching on my personal space all night. In addition, my mouth had that waking-up-in-the-morning taste and my inflatable neck pillow had a hole in it. Fabulous.

Nonetheless, seeing the city lights below made reality more tolerable and, soon after, we landed. When the sun rose, I looked out of the airport windows and saw…mountains. No ocean. No swimming required. Seemed like I was in La Paz…if I needed more proof, all I had to do was breath. With La Paz sitting 13,500 feet above sea level, feeling like I had suddenly developed a heart condition (that left me dizzy and breathless) was another sure sign that I was well on my way to Cochabamba.

**I took this picture as I flew out of La Paz, en route to Santa Cruz (where I caught a flight to Cochabamba).

Though water began to fill the plane, no one, including myself, was afraid, only slightly annoyed at what we had to do: gather our belongings, put on lifejackets, and evacuate. I considered leaving some things behind to evacuate quicker, but I hated the thought of my laptop getting destroyed and hastily gathered my things before heading to the airplane door and exiting via yellow emergency escape slide.

Once outside the plane, we walked the rest of the way to the airport, trudging through the surf. Laptop in hand I explained to some guy walking beside me that I thought something like this would happen and that I regretted not putting my laptop in a plastic bag to safeguard it from the water.

At that point, I woke up and found that, despite the plane still being up in the air and my laptop resting safe in my bag, my surroundings were not nearly as nice as in my dream. Outside, it was dark and, inside the plane, I was sandwiched between the window and a stocky man whose left elbow had been encroaching on my personal space all night. In addition, my mouth had that waking-up-in-the-morning taste and my inflatable neck pillow had a hole in it. Fabulous.

Nonetheless, seeing the city lights below made reality more tolerable and, soon after, we landed. When the sun rose, I looked out of the airport windows and saw…mountains. No ocean. No swimming required. Seemed like I was in La Paz…if I needed more proof, all I had to do was breath. With La Paz sitting 13,500 feet above sea level, feeling like I had suddenly developed a heart condition (that left me dizzy and breathless) was another sure sign that I was well on my way to Cochabamba.

**I took this picture as I flew out of La Paz, en route to Santa Cruz (where I caught a flight to Cochabamba).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)